1.5 Accessibility changes in motorised Estonia

- While motorisation reduces people’s travel options in Estonia’s larger urban regions, a private car ensures access to services in remote areas.

Motorisation is the increase in the frequency of owning and using motor vehicles, and the spread of motor culture in a broader sense.

The first car was driven on Estonian roads in 1896; currently, there are over 740,000 cars in Estonia (Statistics Estonia 2018). Cars are a commodity owned by over half of the country’s inhabitants. On the one hand, using cars has improved the travel options of many people and considerably reduced the perceived distances. On the other hand, the powerful increase in the number of cars has changed the public space in towns as well as elsewhere in Estonia. Motorisation is the increase in the frequency of owning and using motor vehicles, and the spread of motor culture in a broader sense. In sparsely populated rural areas where public transport is insufficient, private cars have become indispensable. In Estonia’s urban regions, the pace in the growth of the number of cars is gradually coming to a halt and there is increasing interest in ideas for planning street space favouring various users. This article discusses motorisation in its two roles: as a facilitator and an inhibitor of access. The aim of the article is to give an overview of how motorisation and the direction of car-based mobility influence access to public services and public space in general for the Estonian population. The article also discusses the strategies for sustainable mobility in.

Mobility is a person’s ability to move from one place to another to meet their daily needs, using one or several modes of transport or transport services.

Mobility is a person’s ability to move from one place to another to meet their daily needs, using one or several modes of transport or transport services. As opposed to traffic planning, which deals with the movement and access of vehicles, mobility planning focuses on the movement of people and goods regardless of the mode of transport. Sustainable mobility means the development of environmentally friendly and sustainable transport for moving people around.

The rapid motorisation of the 1990s is stabilising

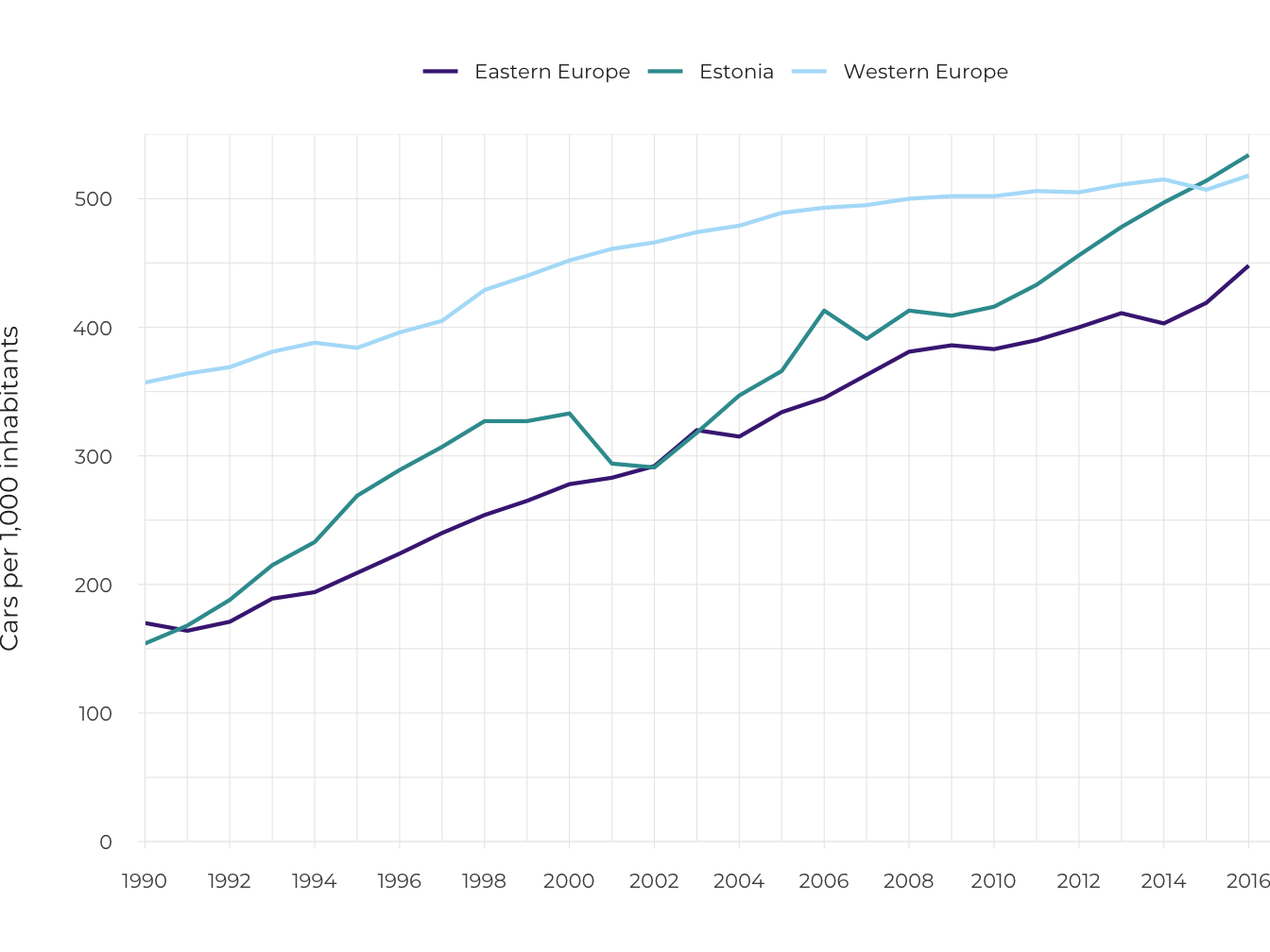

Rapid motorisation in Estonia is similar to that occurring in other Eastern Bloc countries. After World War II, the levels of motorisation measured as the number of cars per 1,000 inhabitants did not differ significantly in Eastern and Western Europe. Just a decade later, the difference was huge. By the early 1990s, motorisation was near a historical peak or had considerably slowed in European Union countries as well as the US, while compensation for the lag that had occurred in Eastern Bloc countries in the previous decades was only beginning. For example, West Germany reached its current level of motorisation in the 1980s, but East Germany reached the same level by the 2000s after German reunification (Pucher and Buehler 2005). In Estonia, the limited availability of private cars during the Soviet period was replaced by an enthusiasm for car ownership in the 1990s. Since then, Estonia has gradually caught up with the level of car use in Western European countries (Figure 1.5.1). Although motorisation continued in Western Europe, the pace of motorisation has been slower there. In terms of the number of registered cars per 1,000 inhabitants, Estonia is currently behind only the most motorised countries of the EU, such as Italy, Luxembourg, Malta and Finland, but has surpassed most of the Western European EU member states.

Figure 1.5.1. Change in motorisation in Western (EU 15) and Eastern European countries (countries that have joined the EU since 2004, except Cyprus and Malta)

## Warning: Ignoring unknown aesthetics: text

Source: Eurostat 2019.

Therefore, the rapid motorisation of Eastern Europe, including Estonia, in the 1990s and 2000s, can be regarded as compensation for the difference caused by political systems. Considering historical motorisation trends (e.g. in the United States), the pace of motorisation will come to a halt sooner or later. The reasons vary, but the bottom line is that everyone who ever wanted to own a car will have acquired one, while every new car user has experienced difficulties with parking space and traffic jams due to the large number of cars. Therefore, the rapid pace of motorisation in previous periods cannot serve as the basis for future predictions and decisions, such as road construction planning.

Motorisation affects the environment, people’s health, mobility and access to services

Motorisation has an environmental impact in terms of energy and land use; it also changes social life and the economic functioning of societies. According to 2017 data from the International Energy Agency, half of the world’s oil output is used for urban and road transport, and the transport sector accounts for over one-quarter of global carbon dioxide emissions. Further to fuel consumption, the environmental impact of motorisation comes from the manufacture and use of cars, traffic hazards, as well as the use of the urban space. As people exercise less when moving around by car, the negative impact of motorisation is also expressed in health conditions, such as obesity and cardiovascular diseases (Bassett et al. 2008). In addition to noise, vibration and pollution via airborne particulate matter in heavy-traffic streets, fewer opportunities for socialising presents another problem for people. Due to motorisation, city streets become ‘traffic pipes’ for cars, which reduce the possibilities available to all other participants in the traffic. The quality of streets as public space has therefore deteriorated.

Accessibility means the opportunities for people to participate in usual social activities.

As streets have often become ‘traffic pipes’, motorisation in cities is beginning to hamper general accessibility. Accessibility means the opportunities for people to participate in usual social activities (Farrington 2007). In addition to the freedom of movement, accessibility covers delivering or planning services and jobs closer to people in order to reduce the need to travel (Figure 1.5.2). Examples of this are the digitalisation of social services and the creation of digital workplaces. Although public services are quite easily accessible online in Estonia without leaving home, social life, the education of children, hobbies and entertainment still require visiting larger towns or city centres. Reducing accessibility to only cover the needs of car users is one-sided, as it reduces travel options and quality for other groups of traffic participants, including pedestrians, cyclists, seniors and people with special needs. For transport planning to take into account a variety of circumstances, an understanding of the role and use of cars in various environments is required: in low-density areas, rural areas, urban regions, and within settlements.

Figure 1.5.2. Elements of accessibility

Source: Discovering Urbanism 2010.

A sustainable urban mobility plan

The purpose of a sustainable mobility plan is to create a sustainable transport system. This means meeting people’s current and future mobility needs using modes of mobility that do not damage the human environment (LiLiA 2017). Such an organisation of mobility requires a convenient public transport network, seamless switching between modes of mobility, development of active modes of mobility (e.g. cycling and walking) and a reduction of the need for cars. The European Commission adopted an action plan on urban mobility in 2009 and supports its implementation at the level of EU member states through the creation of cooperation and knowledge networks, data gathering and financial investments (Eltis 2019).

Life in low-density areas is car-centred

Surveys by the Estonian Road Administration on satisfaction with public transport show that people’s satisfaction with the quality and accessibility of public transport within counties has decreased. Arrival times, routes and connections between routes are the greatest sources of dissatisfaction. Even if the locations of stops and limited departures a day make public transport accessible to a large part of the population (Figure 1.5.3), this does not mean that it can actually compete with car transport in terms of travel time and the number of connections. According to the 2014 survey ‘Satisfaction of inhabitants with local public services’ by Saar Poll, satisfaction with and competitiveness of public transport are higher in towns than in lower-density areas; that is, peri-urban areas and remote areas far from urban centres. In low-density areas, especially in areas of low demand, public transport departures are infrequent and it is difficult for people to time their movements, especially if journeys have to be combined.

Figure 1.5.3. Access to public transport in Estonia (assessed by the nearness of stops and frequency of departures)

## Reading layer `EKSPORT_3301-N0RqvBQsFGT19Q0M-t7' from data source `/Users/taavetkutsar/Documents/GitHub.nosync/EIA_2019/data/15_fig3_data/EKSPORT_3301-N0RqvBQsFGT19Q0M-t7.shp' using driver `ESRI Shapefile'

## Simple feature collection with 4708 features and 7 fields

## geometry type: MULTIPOLYGON

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 369548.3 ymin: 6377141 xmax: 739152.8 ymax: 6617849

## epsg (SRID): NA

## proj4string: +proj=lcc +lat_1=59.33333333333334 +lat_2=58 +lat_0=57.51755393055556 +lon_0=24 +x_0=500000 +y_0=6375000 +ellps=GRS80 +units=m +no_defs## VID KOOD NIMI VAARTUS STAMP_CRE JUHUSLIK GEOKODEER8

## 1 57447852 6536 Põlva linn 21 2020-01-17 0 0

## 2 57447464 8927 Valgesoo küla 76 2020-01-17 0 0

## 3 57444189 1846 Himmaste küla 88 2020-01-17 0 0

## 4 57444228 1609 Eoste küla 87 2020-01-17 0 0

## 5 57446917 7660 Soesaare küla 35 2020-01-17 0 0

## 6 57446719 1081 Adiste küla 49 2020-01-17 0 0

## geometry

## 1 MULTIPOLYGON (((679497.7 64...

## 2 MULTIPOLYGON (((679996.2 64...

## 3 MULTIPOLYGON (((680735.3 64...

## 4 MULTIPOLYGON (((681220.3 64...

## 5 MULTIPOLYGON (((681971.1 64...

## 6 MULTIPOLYGON (((684009.3 64...## Reading layer `Tee' from data source `/Users/taavetkutsar/Documents/GitHub.nosync/EIA_2019/data/15_fig3_data/Tee.shp' using driver `ESRI Shapefile'

## Simple feature collection with 6092 features and 3 fields

## geometry type: LINESTRING

## dimension: XY

## bbox: xmin: 377167.4 ymin: 6381180 xmax: 738908.5 ymax: 6614256

## epsg (SRID): 3301

## proj4string: +proj=lcc +lat_1=58 +lat_2=59.33333333333334 +lat_0=57.51755393055556 +lon_0=24 +x_0=500000 +y_0=6375000 +ellps=GRS80 +units=m +no_defs## NIMETUS TEE_NR TYYP

## 1 Mõniste - Ape 68 Tugimaantee

## 2 Mõniste - Ape 68 Tugimaantee

## 3 Mehka - Vastse-Roosa 25198 Kõrvalmaantee

## 4 Mõniste - Tiitsa - Karisöödi 25199 Kõrvalmaantee

## 5 Mõniste - Tiitsa - Karisöödi 25199 Kõrvalmaantee

## 6 Mehka - Vastse-Roosa 25198 Kõrvalmaantee

## geometry

## 1 LINESTRING (659609.2 638215...

## 2 LINESTRING (659217.9 638423...

## 3 LINESTRING (653878.7 638465...

## 4 LINESTRING (654215.3 638118...

## 5 LINESTRING (651182.3 638504...

## 6 LINESTRING (651198.5 638520...